Photography: Augustine Paredes, Ming Yuan

Untitled (non-cochlear typographic ornament I-VI), 2024

appx. 100 x 100 x 5 cm each

mahogany, oil on cotton

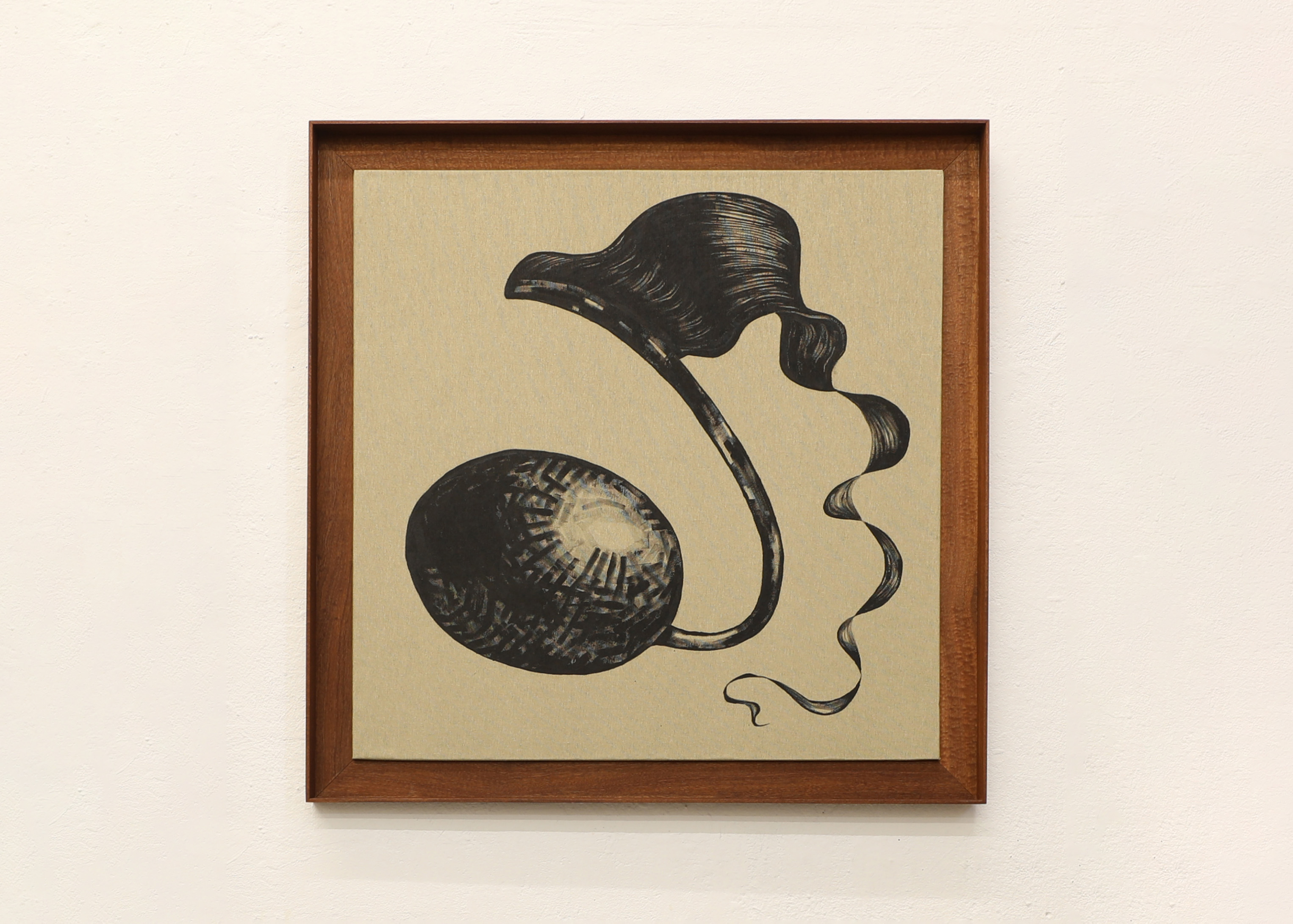

Untitled (non-cochlear typographic ornament VII), 2024

appx. 80 x 60 x 3 cm

mahogany, oil on copper

Untitled (non-cochlear typographic ornament VIII), 2024

appx. 80 x 60 cm

Ink on handmade paper

Edition 10, AP 1

Intermezzo

21th November 2024 ‒ 8th January 2025

Galerie Perpétuel

Text by Teresa Heinzelmann

What would the notes sound like, if one attempted playing them? Though alluding us with the sharp representations of the icon of musical scores, the notes remain illegible since they miss the five lines that establish a commonality for the black dot to become more than a mere black dot. Eighth notes and varying rests are turned decorative, framing the squared canvases as if they were pretty silk scarves instead of the backsides of hard cotton canvas.

Almost renaissance-like brushstrokes neatly line up the notes, and render their saturated black oil paint opaque. Ming Yuan’s reduced formal decisions in colour and form generate a clear overview and a filigran exactness. Set within a square, the notes are pushed to the margins, leaving the middle to blankness. The notes appear to be a frame themselves, echoed by dark mahogany wood. Unable to communicate tonality, they prance along the rim of the canvas, shining like pearls, haughty with their flags high up, gracefully expressing their elegance in shape. They seem to perform what the word decorum stands for: appropriate behavior, the avoidance of anything unseemly or offensive in manner. Reduced to a mere icon, a pure ornament, sitting squarely.

Deprived of tonality, only rhythm remains: relational time, the variations of a snippet of a minute signaled through the eighth notes and various rests. Each sign is repeated up to sixteen times within one painting, abandoning their original function. The symmetric repetition leaves us with nothing but with order, turning them ornamental. This underlying meaning rises to the surface here: ornament, from the Latin ornare, means not only to beautify but also to order.

As the formal musical signs are repeated ornamentally, and not coherently, they don’t come together as a music score or a German Takt. The notes are deprived twice of what they’re made for: neither indicating tonality, nor rhythm. Painting them upside-down and back-to-front enhances this lack of functionality. The notes not only frame emptiness, but are also empty themselves. Thereby, the repetition turns into an orchestrated overload of ordering principles, creating an exaggeration in the minimal. It’s what Kelley described as a ‚ludicrous exaggeration" ‒ an absurdness that comes with the functionless repetition. The paintings thus nearly transform from ornamental graphic scores into caricature of order.

One of the six paintings stands in stark contrast to the others: a single oversized note, like a comical close-up portrait, takes center stage with its flag stretched into a long, untangled curl. The notion of caricature enables an ambivalence, allowing for an uneasiness to creep in, infringing uncannily what seemed so prettily orchestrated. The ornament becomes grotesque. That massive elongation and the crudely sketched notehead questions the other notes’ fine behavior, acting as a satirical interlude̶an Intermezzo̶disrupting the main dramatic act. To be decorative, however neatly and pretty, comes with a pressure to load and to equip oneself to a level of perfection, with a subconscious understanding of oneself as not yet enough. The single note unveils a tangible emancipation from strict order, and her provocation glimpses through the others, too. Having their stem sometimes on the left side of the notehead, theoretically, they won't even be considered notes anymore. They don!t work like they!re meant to, in spite of their overtly order. Ming Yuans Intermezzo sounds between the haughty beauty and the mischievous caricature, when haughty perfection becomes haunting subjection.

21th November 2024 ‒ 8th January 2025

Galerie Perpétuel

Text by Teresa Heinzelmann

What would the notes sound like, if one attempted playing them? Though alluding us with the sharp representations of the icon of musical scores, the notes remain illegible since they miss the five lines that establish a commonality for the black dot to become more than a mere black dot. Eighth notes and varying rests are turned decorative, framing the squared canvases as if they were pretty silk scarves instead of the backsides of hard cotton canvas.

Almost renaissance-like brushstrokes neatly line up the notes, and render their saturated black oil paint opaque. Ming Yuan’s reduced formal decisions in colour and form generate a clear overview and a filigran exactness. Set within a square, the notes are pushed to the margins, leaving the middle to blankness. The notes appear to be a frame themselves, echoed by dark mahogany wood. Unable to communicate tonality, they prance along the rim of the canvas, shining like pearls, haughty with their flags high up, gracefully expressing their elegance in shape. They seem to perform what the word decorum stands for: appropriate behavior, the avoidance of anything unseemly or offensive in manner. Reduced to a mere icon, a pure ornament, sitting squarely.

Deprived of tonality, only rhythm remains: relational time, the variations of a snippet of a minute signaled through the eighth notes and various rests. Each sign is repeated up to sixteen times within one painting, abandoning their original function. The symmetric repetition leaves us with nothing but with order, turning them ornamental. This underlying meaning rises to the surface here: ornament, from the Latin ornare, means not only to beautify but also to order.

As the formal musical signs are repeated ornamentally, and not coherently, they don’t come together as a music score or a German Takt. The notes are deprived twice of what they’re made for: neither indicating tonality, nor rhythm. Painting them upside-down and back-to-front enhances this lack of functionality. The notes not only frame emptiness, but are also empty themselves. Thereby, the repetition turns into an orchestrated overload of ordering principles, creating an exaggeration in the minimal. It’s what Kelley described as a ‚ludicrous exaggeration" ‒ an absurdness that comes with the functionless repetition. The paintings thus nearly transform from ornamental graphic scores into caricature of order.

One of the six paintings stands in stark contrast to the others: a single oversized note, like a comical close-up portrait, takes center stage with its flag stretched into a long, untangled curl. The notion of caricature enables an ambivalence, allowing for an uneasiness to creep in, infringing uncannily what seemed so prettily orchestrated. The ornament becomes grotesque. That massive elongation and the crudely sketched notehead questions the other notes’ fine behavior, acting as a satirical interlude̶an Intermezzo̶disrupting the main dramatic act. To be decorative, however neatly and pretty, comes with a pressure to load and to equip oneself to a level of perfection, with a subconscious understanding of oneself as not yet enough. The single note unveils a tangible emancipation from strict order, and her provocation glimpses through the others, too. Having their stem sometimes on the left side of the notehead, theoretically, they won't even be considered notes anymore. They don!t work like they!re meant to, in spite of their overtly order. Ming Yuans Intermezzo sounds between the haughty beauty and the mischievous caricature, when haughty perfection becomes haunting subjection.